What's in a Name

Customarily we call people to the Torah using their Hebrew names. “Yaamod Shmaryah ben Tzemach v’Masha.” But we go about our days using our English names. “Stand up Steven Moskowitz.”

Except at synagogue, or perhaps at weddings and funerals, we rarely call people by their Hebrew names. So why are people surprised that our patriarch Joseph goes by an Egyptian name instead of the Hebrew name his parents gave him?

The Torah reports: “Pharaoh then gave Joseph the name Zaphenath-paneah.” (Genesis 41) In ancient Egyptian, this means “God speaks; he lives.” First Pharaoh appoints Joseph as his number two, in charge of shepherding Egypt through the impending famine. Then he gives him a proper Egyptian name, as well as a wife, by the way.

Like Joseph we live in two worlds. We carry two names. Our identities are hyphenated. American-Jew. Which name we rely on depends upon the circumstance. Do I identify as a Jew? Or should I be called by my American identity? It depends on who we are standing beside. It depends upon the environment.

The Israeli poet, Zelda, suggests it depends on even more. We have far more than just two names. She writes:

How do we wish to be known?

The rabbis offer an exclamation.

“The crown of a good name is superior to them all.” (Pirke Avot 4)

And that works in Hebrew or in English—and even in Egyptian—or any language for that matter.

It’s really all about earning a good name.

Except at synagogue, or perhaps at weddings and funerals, we rarely call people by their Hebrew names. So why are people surprised that our patriarch Joseph goes by an Egyptian name instead of the Hebrew name his parents gave him?

The Torah reports: “Pharaoh then gave Joseph the name Zaphenath-paneah.” (Genesis 41) In ancient Egyptian, this means “God speaks; he lives.” First Pharaoh appoints Joseph as his number two, in charge of shepherding Egypt through the impending famine. Then he gives him a proper Egyptian name, as well as a wife, by the way.

Like Joseph we live in two worlds. We carry two names. Our identities are hyphenated. American-Jew. Which name we rely on depends upon the circumstance. Do I identify as a Jew? Or should I be called by my American identity? It depends on who we are standing beside. It depends upon the environment.

The Israeli poet, Zelda, suggests it depends on even more. We have far more than just two names. She writes:

Everyone has a nameHer poem is beautiful in its simplicity. It is thought-provoking, and at times haunting. How many encounters, how many circumstances offer us new names? We are left wondering.

given to him by God

and given to him by his parents

Everyone has a name

given to him by his stature

and the way he smiles

and given to him by his clothing

Everyone has a name

given to him by the mountains

and given to him by his walls

Everyone has a name

given to him by the stars

and given to him by his neighbors

Everyone has a name

given to him by his sins

and given to him by his longing

Everyone has a name

given to him by his enemies

and given to him by his love

Everyone has a name

given to him by his feasts

and given to him by his work

Everyone has a name

given to him by the seasons

and given to him by his blindness

Everyone has a name

given to him by the sea and

given to him

by his death.

How do we wish to be known?

The rabbis offer an exclamation.

“The crown of a good name is superior to them all.” (Pirke Avot 4)

And that works in Hebrew or in English—and even in Egyptian—or any language for that matter.

It’s really all about earning a good name.

Let's Be Proud...and Be Careful

Although the true history of Hanukkah recounts a bloody

civil war between Jewish zealots led by Judah Maccabee with their fellow Jews enamored

of Greek culture, we prefer to tell the story of the miracle of oil. Here is that idealized version.

A long time ago, approximately 2,200 years before our

generation, the Syrian-Greeks ruled much of the world and in particular the

land of Israel. Their king, Antiochus,

insisted that all pray and offer sacrifices as he did. He outlawed Jewish practice and desecrated

the holy Temple. But our heroes, the

Maccabees, rebelled against his rule.

After nearly three years of battle, the Maccabees prevailed. They recaptured the Temple.

When the Jews entered the Temple, they were horrified to

discover that their holiest of shrines had been transformed and remade to suit pagan

worship. They declared a dedication (the

meaning of hanukkah) ceremony. Soon

they discovered that there was only enough holy oil to last for one of the

eight day long ceremony. Still they lit

the menorah that adorned the sanctuary.

And lo and behold, a great miracle happened there. The oil lasted not for the expected single

day but for all eight days.

The rabbis therefore decreed that we should light Hanukkah

candles on each of this holiday’s nights, beginning on the first evening, on

the twenty fifth of Kislev. (The customs

of spinning dreidels and eating foods fried in oil came much later.) The rabbis pronounced: “It is a mitzvah to place the Hanukkah lamp at the entrance to one’s house on

the outside, so that all can see it. If a person lives upstairs, he places it at the window most adjacent to

the public domain.” (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 21b)

Contrary to the

contemporary ethic of privacy where what we do in our own homes is not to be

publicized to the outside world, the rabbis instruct us that we must display

the menorah so that others may see it.

Why? So that the world might also

learn about the miracle of Hanukkah. So

that others might see that God performs wonders.

Are not our Jewish

identities meant to be hidden? No, the

rabbis declare. They are intended to be

proclaimed to the world. Even though

everyone else appears to be celebrating other holidays at this time of year, we

reaffirm that we have our own unique faith, and that we are proud to publicize

it. The rabbis counsel that we should

proudly proclaim our Jewish faith—at least during the eight days of

Hanukkah. That is the message of the

Maccabees. That is the import of their

revolt against those who wished to suppress Jewish practice.

But what happens if Jews

live in a time and place when placing the menorah in their windows could be

dangerous? The rabbis decree: “And

in a time of danger he places it on the table and that is sufficient to fulfill

his obligation.” What should we do now? Where should we place the menorah today? Is our own era a time of danger?

Recently I met with a friend who was visiting from

Israel. He told me that he now covers

his kippah with a baseball hat when going out to restaurants in New York. He is afraid.

I heard as well of young couples who second guess their decision to send

their children to a Jewish nursery school for fear that it could be a target of

antisemitic attacks. After years of

increasing attacks, after the most recent Jersey City murders and the assault

at Indiana University to name a few, fear has come to dominate our discussions

of Jewish identity. Where is it safe to

declare our Jewishness?

Should we hide our identity?

Can the Talmud, and Jewish tradition, help us to figure out what

constitutes a real danger? Later

authorities suggest that the rabbis understood danger to mean when Jewish practice

is outlawed, such as during the Maccabean revolt. Only then should we move our menorahs to “safer

ground.” But who gets to decide what

dangerous means? Our rabbis? Our tradition?

Instead it is each of us. Danger is of course a matter of

perception. It is in truth more about

feelings than threats. If a person is afraid,

then the threat is real.

I have been thinking that perhaps my frequent trips to

Israel have provided me with some helpful measures of strength and resolve. The modern era grants us something that our

ancient rabbis could never have imagined: a sovereign Jewish state, a state

that can fight back against our enemies.

We look to a state that can fortify us and offer us even greater courage

in the face of this growing tide of antisemitic hate.

This is why I found it so surprising that it was my Israeli

friend who now expresses fear. Perhaps

it is even more a matter of where one feels at home. If we feel at home we are less likely to feel

afraid.

Today we are called once again to fight back against

antisemitism. Our day demands that we

never allow this hate even the space to breathe. We must stand up. We must be forever proud. But we must also be prudent. The rabbis’ caution is well taken.

The most important point of course is that regardless of

where we decide to place the menorah, regardless of whether or not we are

afraid, we light the candles. Find that

place. Find the place where you are

comfortable proudly declaring your Jewish faith. And there light the menorah. This year most especially, this holiday of

Hanukkah demands no less.

The Kiss of Reconciliation

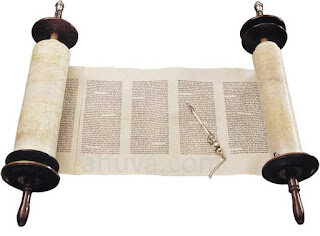

The Torah scroll is beautifully calligraphed. Each of its letters is meticulously drawn. It takes a Torah scribe one year to fashion a single scroll. Some letters have small, stylized crowns. The chapters and verses are perfectly arranged in columns, unfettered by punctuation marks. Although each scroll is different because it is fashioned by a different scribe, the letters and words of every Torah are calligraphed in a similar manner.

“Moses” looks the same in every Torah scroll. There is the mem, the first letter of Moshe. Then the shin, adorned with its crowns, and finally the heh. Like all the other words in the Torah, there are no vowels below the letters or cantillation marks above the letters. In fact, only a very small fraction of words in the Torah have additional notations.

Very few words have marks above the letters. This week we discover one of these unique examples: “Vayishakeyhu—and he kissed him.” Calligraphed above each of its letters is a dot. Here is the story that surrounds this kiss. Our forefather Jacob stole the birthright from his brother Esau. Esau then threatened to kill him. Jacob runs and builds a life for himself with his uncle. He marries (several times) and fathers many children. Now, many years later, the brothers are to be reunited, and we hope, reconciled.

This week we read, “Jacob himself went on ahead and bowed low to the ground seven times until he was near his brother. Esau ran to greet him. He embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept.” (Genesis 33) The brothers appear reconciled. What led to the reconciliation? Was it Jacob’s act of humbling himself before his brother? Was it Esau’s embrace? The seventh century Masoretes, who developed the traditions of calligraphy with which a Torah is scribed, suggest it was the kiss.

Holding his brother close, Esau kissed Jacob and kissed him again and again, until they both wept. The Rabbis concur: “The word ‘kissed’ is dotted above each letter in the Torah’s writing. Rabbi Simeon ben Elazar said: this teaches that Esau felt compassion in that moment and kissed Jacob with all his heart. (Bereshit Rabbah) Reconciliation can only be achieved when people bring their heart—in its entirety. Repair involves compassion for the other. It necessitates forgiveness. And these must derive from the heart.

A kiss can be perfunctory. The Torah’s calligraphy suggests that, in this case it is anything but. A kiss should be punctuated by intention. Here it offers the compassion and forgiveness that leads to the weeping of reconciliation. The brothers stand together.

We are of course the descendants of Jacob. The tradition teaches that our enemies are the descendants of Esau. I wonder if our ancient calligraphers intended to teach that reconciliation between brothers is our most cherished hope and prayer.

Why else would they notate this word in a different manner than all other words?

Embedded in the kiss Esau offers Jacob is our tradition’s hope that the descendants of Esau will one day make peace with the descendants of Jacob. One day, we pray, we might make peace with our enemies, who, our tradition reminds us, are, and will always be, our brothers.

The Torah wishes to punctuate this hope for reconciliation and repair. One day brothers, and all humanity, will be at peace with each other.

And we will embrace, kiss, and finally weep as one family.

“Moses” looks the same in every Torah scroll. There is the mem, the first letter of Moshe. Then the shin, adorned with its crowns, and finally the heh. Like all the other words in the Torah, there are no vowels below the letters or cantillation marks above the letters. In fact, only a very small fraction of words in the Torah have additional notations.

Very few words have marks above the letters. This week we discover one of these unique examples: “Vayishakeyhu—and he kissed him.” Calligraphed above each of its letters is a dot. Here is the story that surrounds this kiss. Our forefather Jacob stole the birthright from his brother Esau. Esau then threatened to kill him. Jacob runs and builds a life for himself with his uncle. He marries (several times) and fathers many children. Now, many years later, the brothers are to be reunited, and we hope, reconciled.

This week we read, “Jacob himself went on ahead and bowed low to the ground seven times until he was near his brother. Esau ran to greet him. He embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept.” (Genesis 33) The brothers appear reconciled. What led to the reconciliation? Was it Jacob’s act of humbling himself before his brother? Was it Esau’s embrace? The seventh century Masoretes, who developed the traditions of calligraphy with which a Torah is scribed, suggest it was the kiss.

Holding his brother close, Esau kissed Jacob and kissed him again and again, until they both wept. The Rabbis concur: “The word ‘kissed’ is dotted above each letter in the Torah’s writing. Rabbi Simeon ben Elazar said: this teaches that Esau felt compassion in that moment and kissed Jacob with all his heart. (Bereshit Rabbah) Reconciliation can only be achieved when people bring their heart—in its entirety. Repair involves compassion for the other. It necessitates forgiveness. And these must derive from the heart.

A kiss can be perfunctory. The Torah’s calligraphy suggests that, in this case it is anything but. A kiss should be punctuated by intention. Here it offers the compassion and forgiveness that leads to the weeping of reconciliation. The brothers stand together.

We are of course the descendants of Jacob. The tradition teaches that our enemies are the descendants of Esau. I wonder if our ancient calligraphers intended to teach that reconciliation between brothers is our most cherished hope and prayer.

Why else would they notate this word in a different manner than all other words?

Embedded in the kiss Esau offers Jacob is our tradition’s hope that the descendants of Esau will one day make peace with the descendants of Jacob. One day, we pray, we might make peace with our enemies, who, our tradition reminds us, are, and will always be, our brothers.

The Torah wishes to punctuate this hope for reconciliation and repair. One day brothers, and all humanity, will be at peace with each other.

And we will embrace, kiss, and finally weep as one family.

Finding Our Shul and Our Path

Among my favorite, and often quoted, books is Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost. (The title alone is enough to get me to pick it up again and again.) Solnit offers a number of observations about travel, nature, science and discovering ourselves. She begins: “Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where you yourself came from, and where you will go.” The question is the beginning of apprehension. (And this is exactly why apprehension has two meanings.) Journeying, and the curiosity that must drive it, leads to wisdom.

Uncertainty is where real learning begins.

Our hero Jacob stands at the precipice of an uncertain time. He is running from home. He has just tricked his brother Esau out of his birthright. Esau has promised to kill him. Their mother, Rebekah, urges Jacob to leave and go to her brother, Laban. Their father Isaac instructs him, “Get up! Go to Paddan-Aram.”

Jacob is alone. He wanders the desert wilderness. Soon he stops for the night. Jacob dreams. He sees angels climbing a ladder that reaches to heaven. He hears God’s voice saying, “I am the Lord, the God of your father Abraham, and your father Isaac. Remember. I am with you.” (Genesis 28). Jacob awakes. He recognizes God’s presence. He has found God in this desolate, and non-descript landscape. He exclaims, “How awesome is this place. This is none other than beth-el, the house of God.”

Rebecca Solnit again. She leans on Tibetan wisdom: “Emptiness is the track on which the centered person moves.” Is it possible, I wonder, that a journey precipitated by feelings of anxiety, bewilderment, and even abandonment (I imagine our forefather thought, “Now my brother wants to kill me. My father tells me to get out. Where am I to go? What am I to do?”) leads to finding one’s bearings? Jacob’s uncertain path is becoming clearer.

In Tibetan, the word for path is “shul.” Solnit continues:

How does our shul not become an “impression of something that used to be there”? If synagogue is only about our imaginations of yesterday, then how do we carve our own path? If authenticity is only driven by what we believe our parents, grandparents, and great grandparents did, and did not do, then how do we create our own impression, in our own image? Too much of what we expect, and want, from our synagogues revolves around the question of how they honor the past. “There is not enough Hebrew at that synagogue” is, for example, a common refrain.

I am thinking. How can we carve a path while looking backward? How do we find our way when looking back, at some impression of yesteryear? How then do we find our own shul?

It is not just a building. It is not as well a destination. It cannot only be the impression made by others, long ago.

It is instead a path.

Jacob awakes, startled, but perhaps more aware. He exclaims, “Surely the Lord is present in this place.”

Where?

Exactly where you are standing.

Just leave the door open.

And heed the voice.

Get up. Go.

Uncertainty is where real learning begins.

Our hero Jacob stands at the precipice of an uncertain time. He is running from home. He has just tricked his brother Esau out of his birthright. Esau has promised to kill him. Their mother, Rebekah, urges Jacob to leave and go to her brother, Laban. Their father Isaac instructs him, “Get up! Go to Paddan-Aram.”

Jacob is alone. He wanders the desert wilderness. Soon he stops for the night. Jacob dreams. He sees angels climbing a ladder that reaches to heaven. He hears God’s voice saying, “I am the Lord, the God of your father Abraham, and your father Isaac. Remember. I am with you.” (Genesis 28). Jacob awakes. He recognizes God’s presence. He has found God in this desolate, and non-descript landscape. He exclaims, “How awesome is this place. This is none other than beth-el, the house of God.”

Rebecca Solnit again. She leans on Tibetan wisdom: “Emptiness is the track on which the centered person moves.” Is it possible, I wonder, that a journey precipitated by feelings of anxiety, bewilderment, and even abandonment (I imagine our forefather thought, “Now my brother wants to kill me. My father tells me to get out. Where am I to go? What am I to do?”) leads to finding one’s bearings? Jacob’s uncertain path is becoming clearer.

In Tibetan, the word for path is “shul.” Solnit continues:

[Shul is] a mark that remains after that which made it has passed by—a footprint, for example. In other contexts, shul is used to describe the scarred hollow in the ground where a house once stood, the channel worn through rock where a river runs in flood, the indentation in the grass where an animal slept last night. All of these are shul: the impression of something that used to be there. A path is a shul because it is an impression in the ground left by the regular tread of feet, which has kept it clear of obstructions and maintained it for the use of others.It seems to me that this is how we also view shul (the Yiddish term for synagogue). It is a path left by others. And now, I am left wondering.

How does our shul not become an “impression of something that used to be there”? If synagogue is only about our imaginations of yesterday, then how do we carve our own path? If authenticity is only driven by what we believe our parents, grandparents, and great grandparents did, and did not do, then how do we create our own impression, in our own image? Too much of what we expect, and want, from our synagogues revolves around the question of how they honor the past. “There is not enough Hebrew at that synagogue” is, for example, a common refrain.

I am thinking. How can we carve a path while looking backward? How do we find our way when looking back, at some impression of yesteryear? How then do we find our own shul?

It is not just a building. It is not as well a destination. It cannot only be the impression made by others, long ago.

It is instead a path.

Jacob awakes, startled, but perhaps more aware. He exclaims, “Surely the Lord is present in this place.”

Where?

Exactly where you are standing.

Just leave the door open.

And heed the voice.

Get up. Go.

Thanksgiving Poems

As we prepare to gather with family and friends in celebration of Thanksgiving and give thanks for the plentiful food, and wine, arranged before us, we pause to acknowledge the privilege and blessing of calling this country our home.

I turn to my poetry books. Recently I discovered Samuel Menashe.

Samuel Menashe was born in New York City in 1925 to Russian Jewish immigrants. He served in the United States infantry during World War II and fought at the Battle of the Bulge. After taking advantage of the GI bill, he traveled to France and earned his PhD from the Sorbonne. Later he taught poetry and literature at CW Post College. He died in 2011. He is a relatively unknown American poet.

Perhaps reading his poetry might help to remind me of how America has inspired Jews and given rise to untold Jewish creativity. His poems, at times feel playful, but then again religious.

I offer three poems:

I turn to my poetry books. Recently I discovered Samuel Menashe.

Samuel Menashe was born in New York City in 1925 to Russian Jewish immigrants. He served in the United States infantry during World War II and fought at the Battle of the Bulge. After taking advantage of the GI bill, he traveled to France and earned his PhD from the Sorbonne. Later he taught poetry and literature at CW Post College. He died in 2011. He is a relatively unknown American poet.

Perhaps reading his poetry might help to remind me of how America has inspired Jews and given rise to untold Jewish creativity. His poems, at times feel playful, but then again religious.

I offer three poems:

LeavetakingEach day is indeed a blessing. Every day is an occasion for giving thanks.

Dusk of the year

Nightfalling leaves

More than we knew

Abounded on trees

We now see through

Hallelujah

Eyes open to praise

The play of light

Upon the ceiling—

While still abed raise

The roof this morning

Rejoice as you please

Your Maker who made

This day while you slept,

Who gives you grace and ease,

Whose promise is kept.

‘Let them sing for joy upon their beds.’— Psalm 149

Now

There is never an end to loss, or hope

I give up the ghost for which I grope

Over and over again saying Amen

To all that does or does not happen—

The eternal event is now, not when.

At What Age are We Called Wise?

If we pray every day and offer the tradition’s prescribed set of prayers, we begin with the singing of psalms and the recitation of blessings. The prayer book’s philosophy is that a soul can be both fortified, and unburdened, by the shouting of blessings and praises for our God. Only then do we move on to our requests. And the very first request we make of God is the following:

Why begin our litany of requests by asking for knowledge, insight and wisdom? Knowledge is something that is gained by study and learning. Insight, which other prayer books translate as understanding, is something that is acquired after much discussion and thought. And wisdom is attained only after years and years of experience.

Perhaps we begin with these words because the rabbis who authored these prayers believed that all knowledge, insight and wisdom begin with God. I now wonder. Can a prayer really be a prayer if it does not connect the mind to the spirit? In the Judaism that I love, and teach, head and heart must be combined. There should be a unity of thought and deed. I stand against thoughtless actions.

Then again, I find that my mind often wanders during our prayers. I discover myself singing the words but thinking of the day’s events or my weekend’s plans. I sing “Adon olam asher malach…” but my thoughts turn to the morning’s bike ride (I crushed that hill) or the evening’s dinner plans (I am looking forward to the tuna sashimi).

Is the unity of thought and deed possible all the time, in every moment?

I pray again, “God, please grant us wisdom, insight and knowledge.”

It is a never ending struggle. It is a daily endeavor. Can knowledge, insight and wisdom be granted by God? Are they not in our hands? Perhaps this first request, this first prayer is a reminder of what I must do each and every day. Commit myself anew to the attainment of knowledge. Read something new. Of insight. Ponder the words I read again and again. But wisdom?

This cannot be achieved in a single moment, or by the performance of a solitary act. It is not acquired by carefully reading a certain book, no matter how important or holy that book might be. Even though the Torah is read again and again, and over and over, wisdom still eludes us.

Wisdom is gained only after years and years. It is the sum total of countless experiences. Can a twenty year old ever be called wise? Can a fifty year old really be imbued with wisdom?

At what age is one be deemed wise?

At seventy? At eighty three? A hundred and twenty?

We read, “Abraham was now old, advanced in years.” (Genesis 24) In Hebrew, zaken, old is associated with wisdom. The rabbis teach that zaken points to an acronym, “zeh kanah hokhmah—this one has acquired wisdom.” Old is not a measure of years but instead a sign of wisdom. Zaken does not mean aged but wise.

And how old is Abraham? 175 years.

I have acquired this knowledge. I have gained this insight. I have achieved this wisdom.

Each of us has many, many more years to go before attaining wisdom and before being called, zaken.

You grace humans with knowledge and teach mortals understanding. Graciously share with us Your wisdom, insight and knowledge. Blessed are You, Adonai, who graces us with knowledge.Before asking for health or even forgiveness, we beseech God, and say, “Please grant us wisdom, insight and knowledge.” This is a curious place to begin. Why is this the first of our asks? Why begin the emotional exercise of prayer with a request for the intellect?

Why begin our litany of requests by asking for knowledge, insight and wisdom? Knowledge is something that is gained by study and learning. Insight, which other prayer books translate as understanding, is something that is acquired after much discussion and thought. And wisdom is attained only after years and years of experience.

Perhaps we begin with these words because the rabbis who authored these prayers believed that all knowledge, insight and wisdom begin with God. I now wonder. Can a prayer really be a prayer if it does not connect the mind to the spirit? In the Judaism that I love, and teach, head and heart must be combined. There should be a unity of thought and deed. I stand against thoughtless actions.

Then again, I find that my mind often wanders during our prayers. I discover myself singing the words but thinking of the day’s events or my weekend’s plans. I sing “Adon olam asher malach…” but my thoughts turn to the morning’s bike ride (I crushed that hill) or the evening’s dinner plans (I am looking forward to the tuna sashimi).

Is the unity of thought and deed possible all the time, in every moment?

I pray again, “God, please grant us wisdom, insight and knowledge.”

It is a never ending struggle. It is a daily endeavor. Can knowledge, insight and wisdom be granted by God? Are they not in our hands? Perhaps this first request, this first prayer is a reminder of what I must do each and every day. Commit myself anew to the attainment of knowledge. Read something new. Of insight. Ponder the words I read again and again. But wisdom?

This cannot be achieved in a single moment, or by the performance of a solitary act. It is not acquired by carefully reading a certain book, no matter how important or holy that book might be. Even though the Torah is read again and again, and over and over, wisdom still eludes us.

Wisdom is gained only after years and years. It is the sum total of countless experiences. Can a twenty year old ever be called wise? Can a fifty year old really be imbued with wisdom?

At what age is one be deemed wise?

At seventy? At eighty three? A hundred and twenty?

We read, “Abraham was now old, advanced in years.” (Genesis 24) In Hebrew, zaken, old is associated with wisdom. The rabbis teach that zaken points to an acronym, “zeh kanah hokhmah—this one has acquired wisdom.” Old is not a measure of years but instead a sign of wisdom. Zaken does not mean aged but wise.

And how old is Abraham? 175 years.

I have acquired this knowledge. I have gained this insight. I have achieved this wisdom.

Each of us has many, many more years to go before attaining wisdom and before being called, zaken.

No Retreat from the World

I retreat to the Torah. It is a welcome distraction from the news and our country’s painful divisions.

This week we read about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. These cities are marked by sinfulness. As in the story of Noah, God decides to start all over and wipe out the sinfulness. Again God shares the plan with a chosen, and trusted, person. This time it is Abraham. God says, “Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do?” (Genesis 18)

God reveals the plan to Abraham. But Abraham pleads in behalf of the people. Abraham argues (and negotiates) with God exacting a promise that if ten righteous people can be found then the cities should be saved. In the end Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed. By the way, some suggest is the origin of the required number of ten for a minyan.

And yet the Torah is unclear about what these cities’ inhabitants did that was so terrible. What were their sins? We are given only hints. “The outrage of Sodom and Gomorrah is so great, and their sin so grave!” Throughout the ages commentators have suggested that the people were guilty of sexual depravity. They cite as evidence the accompanying story that the townspeople attempted to rape the divine messengers who visit Lot, a resident of Sodom and a nephew of Abraham. This explains the English term “sodomy.”

Later the prophet Ezekiel offers more detail: “Only this was the sin of your sister city Sodom: arrogance! She and her daughters had plenty of bread and untroubled tranquility; yet she did not support the poor and needy.” (Ezekiel 16) He sees their sin in social terms. The cities were destroyed because of their failure to reach out to the needy and most vulnerable. There was plenty of food to share and yet they kept it all to themselves.

They were arrogant. They felt themselves superior. They shared little with the hungry. They turned a blind eye to those in need.

The rabbis expand upon the prophet Ezekiel’s understanding. They saw the cities’ sinfulness in their treatment of others, most especially their failure to fulfill the mitzvah of hospitality and welcoming the stranger. They argue that this sin would have been understandable if Sodom and Gomorrah were poor cities, but they were in fact wealthy. The rabbis weave a story describing the streets of these cities as paved with gold. They taught that the cities’ inhabitants flooded the cities’ gates in an effort to prevent strangers from entering and finding refuge there.

In the rabbinic imagination, the cities were destroyed because of their own moral lapses. They were affluent. There was plenty of food for them to eat. Yet they did not share it with anyone. They hoarded it for themselves. They prevented strangers from entering their cities. They thought only of their own welfare and their own livelihood.

I hear Rabbi Gunther Plaut teaching, “The treatment accorded newcomers and strangers was then and may always be considered a touchstone of a community’s moral condition.”

And I am left to wonder. Can any retreat be found?

I search in vain for distractions.

The Torah appears to speak of today. It continues to speak to today.

That is its most important, and powerful, voice.

Perhaps I should give up the search…for distractions.

This week we read about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. These cities are marked by sinfulness. As in the story of Noah, God decides to start all over and wipe out the sinfulness. Again God shares the plan with a chosen, and trusted, person. This time it is Abraham. God says, “Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do?” (Genesis 18)

God reveals the plan to Abraham. But Abraham pleads in behalf of the people. Abraham argues (and negotiates) with God exacting a promise that if ten righteous people can be found then the cities should be saved. In the end Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed. By the way, some suggest is the origin of the required number of ten for a minyan.

And yet the Torah is unclear about what these cities’ inhabitants did that was so terrible. What were their sins? We are given only hints. “The outrage of Sodom and Gomorrah is so great, and their sin so grave!” Throughout the ages commentators have suggested that the people were guilty of sexual depravity. They cite as evidence the accompanying story that the townspeople attempted to rape the divine messengers who visit Lot, a resident of Sodom and a nephew of Abraham. This explains the English term “sodomy.”

Later the prophet Ezekiel offers more detail: “Only this was the sin of your sister city Sodom: arrogance! She and her daughters had plenty of bread and untroubled tranquility; yet she did not support the poor and needy.” (Ezekiel 16) He sees their sin in social terms. The cities were destroyed because of their failure to reach out to the needy and most vulnerable. There was plenty of food to share and yet they kept it all to themselves.

They were arrogant. They felt themselves superior. They shared little with the hungry. They turned a blind eye to those in need.

The rabbis expand upon the prophet Ezekiel’s understanding. They saw the cities’ sinfulness in their treatment of others, most especially their failure to fulfill the mitzvah of hospitality and welcoming the stranger. They argue that this sin would have been understandable if Sodom and Gomorrah were poor cities, but they were in fact wealthy. The rabbis weave a story describing the streets of these cities as paved with gold. They taught that the cities’ inhabitants flooded the cities’ gates in an effort to prevent strangers from entering and finding refuge there.

In the rabbinic imagination, the cities were destroyed because of their own moral lapses. They were affluent. There was plenty of food for them to eat. Yet they did not share it with anyone. They hoarded it for themselves. They prevented strangers from entering their cities. They thought only of their own welfare and their own livelihood.

I hear Rabbi Gunther Plaut teaching, “The treatment accorded newcomers and strangers was then and may always be considered a touchstone of a community’s moral condition.”

And I am left to wonder. Can any retreat be found?

I search in vain for distractions.

The Torah appears to speak of today. It continues to speak to today.

That is its most important, and powerful, voice.

Perhaps I should give up the search…for distractions.

Two States for Two Peoples

Last week I attended JStreet’s National Conference in Washington DC. What follows are some of my impressions. First a word about JStreet’s mission. JStreet was founded a little over ten years ago to advocate for, and lobby in behalf of, a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In other words, it supports the creation of a Palestinian state in a large portion of the West Bank, as well as perhaps Gaza, living alongside the Jewish State of Israel. AIPAC by contrast, although officially affirming the need for two states, avoids prescribing a solution to this conflict, claiming instead that this is for Israelis, and Palestinians, to decide. AIPAC’s mission is to make sure there is strong bipartisan support for Israel, and in particular for Israel’s security, in the United States Congress.

I will also be attending the AIPAC Policy Conference the beginning of March. Unlike AIPAC which both Democrats and Republicans attend, there were only senators and representatives from the Democratic Party at JStreet. There were also only Israelis from the center and left in attendance. While I recognize that many find JStreet controversial I struggle to understand why it is deemed out of bounds. Among those in attendance, and those who spoke to the 4,000 participants, were Ehud Barak, former Prime Minister and Israel Defense Forces chief of staff, and Ami Ayalon, former director of Shin Bet (Israel’s internal security service) and admiral in Israel’s navy. Their security credentials are unmatched. More about that later. First a few details about my personal journey regarding the question of two states for two peoples.

I have long believed that the two state solution is the only answer, albeit an imperfect one, to the conflict....

I will also be attending the AIPAC Policy Conference the beginning of March. Unlike AIPAC which both Democrats and Republicans attend, there were only senators and representatives from the Democratic Party at JStreet. There were also only Israelis from the center and left in attendance. While I recognize that many find JStreet controversial I struggle to understand why it is deemed out of bounds. Among those in attendance, and those who spoke to the 4,000 participants, were Ehud Barak, former Prime Minister and Israel Defense Forces chief of staff, and Ami Ayalon, former director of Shin Bet (Israel’s internal security service) and admiral in Israel’s navy. Their security credentials are unmatched. More about that later. First a few details about my personal journey regarding the question of two states for two peoples.

I have long believed that the two state solution is the only answer, albeit an imperfect one, to the conflict....

Road Trips

One of the most important discussions on any journey, most especially a road trip, is where to make stops. “We’re coming up on a rest stop, does anyone need to use the bathroom?” is a frequently heard question. And, “No,” is the typical response, most especially when your passengers are fixated on watching their YouTube videos. And then five minutes later, after flying past Molly Pitcher (do I hear any cheers for the Jersey Turnpike?), a small voice is heard, “I have to go to the bathroom.” And now, you are twenty minutes from the next rest stop, assuming the ideal, and unrealistic, scenario that the Turnpike is empty of traffic, and you have to make an unscheduled stop.

Or the fuel light comes on, and it is time to refill the gas tank. Or the passengers complain that they are hungry, or they appear cranky, and you decide that everyone needs a break, a chance to stretch their legs, and an escape from the crowded car. “Ten minutes and then we are back on the road,” you shout as they bolt out their seats.

But here is exactly where the adventure might begin. Here is where a discovery might occur. Where the destination is delayed, a story often breaks free.

“Then Abram journeyed by stages toward the Negev.” (Genesis 12)

And I am left wondering about those stages. Where did our forefather stop? What caused him to delay? What place grabbed hold of his heart, or his imagination, and called to him, “We should camp here. We should pause in this place.”

I am certain some of these unforeseen stops, and stages, were made for the most mundane, and routine, of reasons. Even in ancient times, someone must have shouted about a bathroom break. Or the animals needed to rest. Or the food and water had to be replenished. Or, our ancestors were simply tired and exhausted and they could drive on no further. Other times, I would like to imagine, there was something about the place, or the people they encountered on their adventure, that made Abram and Sarai stay longer. “In this place, we should take our time. We should linger.”

So much of our lives are spent searching for a goal and heading toward a destination. So much of our lives are encapsulated by that often heard statement, “Ten minutes and then we are back on the road.” Life is truly lived not in these achieved destinations, but in the stages, and pauses, taken along the way. Meaning is found in the steps discovered along the journey. Life is in some very important ways about the pit stops.

It is in the unexpected conversations found, in the chance meeting made on our way to something else.

And so I am now wondering what it would be like to travel the world without purchasing a return ticket home. I wonder what it might be like to see the world not according to some prearranged itinerary (“Day one: the temples of Kyoto.”), but instead to see what place might call to you and what site might beg you to linger.

For two thousand years the Jewish people have prayed, and in many ages, hoped beyond any realistic hope, that we might return to the land of Israel. This was, and still is, our destination. It figures in so many of our prayers. And now we are there. But there were so many stages along this journey. We built homes in Russia, Iraq, France and Syria. We founded communities in Spain, Turkey, England or America just to name a few. In some of these places there is no longer a Jewish presence and in others we are still there, journeying. We are still lingering.

And now I realize. This is what must define us: the pauses, and the unexpected turns. How is it that your family made their way to this place and found itself in this home? Look back on your own personal stories and histories. Was everything so carefully planned? Or did they only have enough money to make it to New York and no further. And so they stayed, and lingered.

Those stops might be as important as the final, intended, destination.

So next time, don’t just run in and out of the rest stop so you can get back on the road as quickly as possible. Linger. And learn.

The truth is arriving offers far less journeying. And learning is perhaps best discovered when lingering.

The stages have always defined us.

Or the fuel light comes on, and it is time to refill the gas tank. Or the passengers complain that they are hungry, or they appear cranky, and you decide that everyone needs a break, a chance to stretch their legs, and an escape from the crowded car. “Ten minutes and then we are back on the road,” you shout as they bolt out their seats.

But here is exactly where the adventure might begin. Here is where a discovery might occur. Where the destination is delayed, a story often breaks free.

“Then Abram journeyed by stages toward the Negev.” (Genesis 12)

And I am left wondering about those stages. Where did our forefather stop? What caused him to delay? What place grabbed hold of his heart, or his imagination, and called to him, “We should camp here. We should pause in this place.”

I am certain some of these unforeseen stops, and stages, were made for the most mundane, and routine, of reasons. Even in ancient times, someone must have shouted about a bathroom break. Or the animals needed to rest. Or the food and water had to be replenished. Or, our ancestors were simply tired and exhausted and they could drive on no further. Other times, I would like to imagine, there was something about the place, or the people they encountered on their adventure, that made Abram and Sarai stay longer. “In this place, we should take our time. We should linger.”

So much of our lives are spent searching for a goal and heading toward a destination. So much of our lives are encapsulated by that often heard statement, “Ten minutes and then we are back on the road.” Life is truly lived not in these achieved destinations, but in the stages, and pauses, taken along the way. Meaning is found in the steps discovered along the journey. Life is in some very important ways about the pit stops.

It is in the unexpected conversations found, in the chance meeting made on our way to something else.

And so I am now wondering what it would be like to travel the world without purchasing a return ticket home. I wonder what it might be like to see the world not according to some prearranged itinerary (“Day one: the temples of Kyoto.”), but instead to see what place might call to you and what site might beg you to linger.

For two thousand years the Jewish people have prayed, and in many ages, hoped beyond any realistic hope, that we might return to the land of Israel. This was, and still is, our destination. It figures in so many of our prayers. And now we are there. But there were so many stages along this journey. We built homes in Russia, Iraq, France and Syria. We founded communities in Spain, Turkey, England or America just to name a few. In some of these places there is no longer a Jewish presence and in others we are still there, journeying. We are still lingering.

And now I realize. This is what must define us: the pauses, and the unexpected turns. How is it that your family made their way to this place and found itself in this home? Look back on your own personal stories and histories. Was everything so carefully planned? Or did they only have enough money to make it to New York and no further. And so they stayed, and lingered.

Those stops might be as important as the final, intended, destination.

So next time, don’t just run in and out of the rest stop so you can get back on the road as quickly as possible. Linger. And learn.

The truth is arriving offers far less journeying. And learning is perhaps best discovered when lingering.

The stages have always defined us.

Save Yourself?

There is a Yiddish expression, tzaddik im peltz, meaning a righteous person in a fur coat. It is a curious phrase.

The great Hasidic rabbi, Menahem Mendl of Kotzk, offers an illustration. When one is cold at home, there are two ways to become warm. One can heat the home or get dressed in a fur coat. The difference between the two is that in the first case the entire house is warmed and everyone sitting in it feels comfortable. Whereas in the second case only the person wearing the coat feels warm, but everyone else continues to freeze.

Righteousness is meant to warm others. It is not meant to warm the soul of the person who performs the righteous deeds. Too often people clothe themselves in good deeds. They hold their heads high and wrap themselves in comforting thoughts. “Look at the good I have done.” They warm themselves in a coat of righteousness.

The task, however, is to build a fire. We are called to bring warmth and healing to others.

A coat of righteousness does no good unless it is wrapped around others.

The Torah relates: “Noah was a righteous man; he was blameless in his age; and Noah walked with God.” (Genesis 6)

God informs Noah that the world, and all its inhabitants, will be destroyed because of its wickedness. So God instructs Noah to build an ark to save two animals of every species as well as his own family. I am left wondering. There is no another righteous person in the world? Noah was the only one?

Apparently Noah agrees with this evaluation. The world is about to be destroyed and Noah offers no argument. He offers no protest. Perhaps he does believe he is indeed the only righteous person in the world.

So God says, “Noah, save yourself.”

And now Noah appears to me as a tzaddik im peltz. The rabbis attempt to suggest that he really builds fires. They suggest Noah takes his time building the ark. He makes sure to do the building where everyone can see the project. The ark was meant not so much to save his family and all the animals but instead as a sign. People were meant to see the ark and repent of their evil ways. But they of course ignore the sign and continue with their lives as if nothing is wrong.

And we continue to walk amid all the signs, amid the fires and floods. We look away from the signs of our potential destruction. We wrap ourselves in fur coats, warming ourselves and proclaiming our righteousness, but doing little more than Noah. We build an ark for ourselves and our families.

I wish to be more than a tzaddik im peltz.

The great Hasidic rabbi, Menahem Mendl of Kotzk, offers an illustration. When one is cold at home, there are two ways to become warm. One can heat the home or get dressed in a fur coat. The difference between the two is that in the first case the entire house is warmed and everyone sitting in it feels comfortable. Whereas in the second case only the person wearing the coat feels warm, but everyone else continues to freeze.

Righteousness is meant to warm others. It is not meant to warm the soul of the person who performs the righteous deeds. Too often people clothe themselves in good deeds. They hold their heads high and wrap themselves in comforting thoughts. “Look at the good I have done.” They warm themselves in a coat of righteousness.

The task, however, is to build a fire. We are called to bring warmth and healing to others.

A coat of righteousness does no good unless it is wrapped around others.

The Torah relates: “Noah was a righteous man; he was blameless in his age; and Noah walked with God.” (Genesis 6)

God informs Noah that the world, and all its inhabitants, will be destroyed because of its wickedness. So God instructs Noah to build an ark to save two animals of every species as well as his own family. I am left wondering. There is no another righteous person in the world? Noah was the only one?

Apparently Noah agrees with this evaluation. The world is about to be destroyed and Noah offers no argument. He offers no protest. Perhaps he does believe he is indeed the only righteous person in the world.

So God says, “Noah, save yourself.”

And now Noah appears to me as a tzaddik im peltz. The rabbis attempt to suggest that he really builds fires. They suggest Noah takes his time building the ark. He makes sure to do the building where everyone can see the project. The ark was meant not so much to save his family and all the animals but instead as a sign. People were meant to see the ark and repent of their evil ways. But they of course ignore the sign and continue with their lives as if nothing is wrong.

And we continue to walk amid all the signs, amid the fires and floods. We look away from the signs of our potential destruction. We wrap ourselves in fur coats, warming ourselves and proclaiming our righteousness, but doing little more than Noah. We build an ark for ourselves and our families.

I wish to be more than a tzaddik im peltz.

All Over Again!?

We have to read the Torah all over again? We have to read the creation story once more?

This week we begin reading the Torah all over again. Our celebrations of Simhat Torah are now in the rear view mirror. Once more we open the Bible’s pages to the story of the world’s creation. We read about Adam and Eve, Noah’s ark, and Abraham and Sarah. We read all over again about the exodus from Egypt, the revelation at Sinai, forty years of wandering, the building of the tabernacle, and the Torah’s many laws and commandments. Before we know it we will unroll the scroll and read about Moses’ death.

But why do this year after year? Why read the same book, the same chapters and the same verses over and over again? In almost every other instance once we read a book, we put it aside. If we really like the story we might give it to a friend. If we deem it a masterpiece, we might grant it an exalted place on our bookshelves. But not with the Torah.

As soon as we finish it, we turn back to the beginning. We read the same story all over again, again and again, year after year. Why?

The answer is simple, yet profound. There is a power to beginning all over again. There is a faith that even though we read these same pages last year, this year we might uncover some new truth. Last year I could have missed something. Last time I read it, perhaps my focus was lacking during that week’s reading. This year some new truth might become revealed.

This year I may in fact find those elusive answers to life’s many questions. I may discover added meaning.

To begin again, to begin anew, offers promise. This year is going to be better. This year something new, and different, might be revealed. Even though I don’t feel any closer, despite years and years of study and learning, I open the book once again with renewed hope.

That is why we never let go of this seeming repetitious assignment. This is why we refuse to look at the Torah as any other book. We are determined that it must not, it cannot remain on our bookshelves among even our most cherished volumes. It must be read, again and again.

This year something might be revealed. This year something new might be discovered. This year, a truth might become illuminated. We open the book once again.

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth…”

Our hope is restored.

A new truth awaits us.

This week we begin reading the Torah all over again. Our celebrations of Simhat Torah are now in the rear view mirror. Once more we open the Bible’s pages to the story of the world’s creation. We read about Adam and Eve, Noah’s ark, and Abraham and Sarah. We read all over again about the exodus from Egypt, the revelation at Sinai, forty years of wandering, the building of the tabernacle, and the Torah’s many laws and commandments. Before we know it we will unroll the scroll and read about Moses’ death.

But why do this year after year? Why read the same book, the same chapters and the same verses over and over again? In almost every other instance once we read a book, we put it aside. If we really like the story we might give it to a friend. If we deem it a masterpiece, we might grant it an exalted place on our bookshelves. But not with the Torah.

As soon as we finish it, we turn back to the beginning. We read the same story all over again, again and again, year after year. Why?

The answer is simple, yet profound. There is a power to beginning all over again. There is a faith that even though we read these same pages last year, this year we might uncover some new truth. Last year I could have missed something. Last time I read it, perhaps my focus was lacking during that week’s reading. This year some new truth might become revealed.

This year I may in fact find those elusive answers to life’s many questions. I may discover added meaning.

To begin again, to begin anew, offers promise. This year is going to be better. This year something new, and different, might be revealed. Even though I don’t feel any closer, despite years and years of study and learning, I open the book once again with renewed hope.

That is why we never let go of this seeming repetitious assignment. This is why we refuse to look at the Torah as any other book. We are determined that it must not, it cannot remain on our bookshelves among even our most cherished volumes. It must be read, again and again.

This year something might be revealed. This year something new might be discovered. This year, a truth might become illuminated. We open the book once again.

“In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth…”

Our hope is restored.

A new truth awaits us.

Some More Kisses

The Torah is of course what we most prize and deem most holy.

Some people were upset because they did not get a chance to kiss the Torah scrolls this past Yom Kippur. Unfortunately, there was a traffic jam in the sanctuary’s middle aisle. I therefore decided it would be best to avoid the congestion and take the Torah scrolls around the outer aisles. A number of people were unable to kiss the Torah and shared their disappointment with me after services. I am really sorry.

I underestimated the power and importance of this ritual. Now I want to take a few moments to think more deeply about this custom. First a clarification. Actually we don’t kiss the Torah. Instead we allow it to give us a kiss. We touch our hand, or prayerbook, or tallis to the scroll and then touch our lips. This custom is the same as that for a mezuzah. When entering our homes, we reach up, touch our fingertips to the mezuzah and then touch our hand to our lips.

We don’t kiss the mezuzah or the Torah. We allow these holy objects to kiss us. We allow them to offer us a measure of their holiness.

We are not nearly as holy as these sacred objects. The Torah is more holy than we are. Or is it? Torah cannot really be Torah without us. It needs us.

We must read it. We must study it. We must discuss it and debate it. If it were obvious what the Torah always said or meant, then there would be no need for interpretation, there would be no need for the volumes and volumes of holy books, spanning thousands of years. There would be no need for…rabbis. What makes Torah Torah is our relationship to it.

We do not worship it. We do not hold it up as an amulet. We must carry it. We dance among its verses. We discover ourselves in its chapters.

We touch it so that we may take some of its holiness into our lives. That task is actually a daily endeavor. We touch it and allow it to give us a kiss so that we might be reminded that we must take more Torah into our lives—always. To touch the Torah is to remind us of what is our holiest task. To do better. To bring a measure of healing to the world around us.

We need the Torah to carry us as much as it needs us to carry it.

Still, on Simhat Torah, everyone and anyone who wants can again have an opportunity to kiss the Torah and even dance with these scrolls. Come to Simhat Torah services and grab this additional opportunity. Even though Yom Kippur is the more widely observed Jewish holiday, Simhat Torah is the more quintessential day. On it we sing and dance. We rejoice and feast. What could be more Jewish than a party?

On this day we remind ourselves that holding the Torah close to our hearts is our most important task. On Simhat Torah we endeavor to take more Torah into our lives.

And some extra kisses never hurt to remind us of this task.

Some people were upset because they did not get a chance to kiss the Torah scrolls this past Yom Kippur. Unfortunately, there was a traffic jam in the sanctuary’s middle aisle. I therefore decided it would be best to avoid the congestion and take the Torah scrolls around the outer aisles. A number of people were unable to kiss the Torah and shared their disappointment with me after services. I am really sorry.

I underestimated the power and importance of this ritual. Now I want to take a few moments to think more deeply about this custom. First a clarification. Actually we don’t kiss the Torah. Instead we allow it to give us a kiss. We touch our hand, or prayerbook, or tallis to the scroll and then touch our lips. This custom is the same as that for a mezuzah. When entering our homes, we reach up, touch our fingertips to the mezuzah and then touch our hand to our lips.

We don’t kiss the mezuzah or the Torah. We allow these holy objects to kiss us. We allow them to offer us a measure of their holiness.

We are not nearly as holy as these sacred objects. The Torah is more holy than we are. Or is it? Torah cannot really be Torah without us. It needs us.

We must read it. We must study it. We must discuss it and debate it. If it were obvious what the Torah always said or meant, then there would be no need for interpretation, there would be no need for the volumes and volumes of holy books, spanning thousands of years. There would be no need for…rabbis. What makes Torah Torah is our relationship to it.

We do not worship it. We do not hold it up as an amulet. We must carry it. We dance among its verses. We discover ourselves in its chapters.

We touch it so that we may take some of its holiness into our lives. That task is actually a daily endeavor. We touch it and allow it to give us a kiss so that we might be reminded that we must take more Torah into our lives—always. To touch the Torah is to remind us of what is our holiest task. To do better. To bring a measure of healing to the world around us.

We need the Torah to carry us as much as it needs us to carry it.

Still, on Simhat Torah, everyone and anyone who wants can again have an opportunity to kiss the Torah and even dance with these scrolls. Come to Simhat Torah services and grab this additional opportunity. Even though Yom Kippur is the more widely observed Jewish holiday, Simhat Torah is the more quintessential day. On it we sing and dance. We rejoice and feast. What could be more Jewish than a party?

On this day we remind ourselves that holding the Torah close to our hearts is our most important task. On Simhat Torah we endeavor to take more Torah into our lives.

And some extra kisses never hurt to remind us of this task.

Keep the Gates Open

I often complain about the holiday schedule, especially during this time of year. Why put two major holidays one week apart from each other? And then as soon as we finish the Yom Kippur fast, ask us to build a sukkah and celebrate this week long festival. And finally, command us to rejoice and celebrate with great revelry the holiday of Simhat Torah, marking the start of the Torah reading cycle all over again. Would it not have been better to spread the holidays out? Perhaps we could even have Rosh Hashanah in the fall and then Yom Kippur in the spring.

Such choices are of course not in our hands. And so one major holiday comes in quick succession, one right after another. We barely have enough time to come up for air. We turn from the beating of our chests and recounting of our sins on Yom Kippur to the banging of hammers as we put up our sukkahs and then the hosting of elaborate get-togethers in these temporary booths which signify the Israelites wandering through the desert wilderness. Why do we so quickly move from one major holiday to another? Why is this Hebrew month of Tishrei so demanding?

We only just gathered for the beautiful and concluding Yom Kippur Neilah service. As the gates of repentance are about to close, we prayed, “Open for us the gates of repentance and return, that we may enter and offer our best. Open for us the gates of forgiveness, that we may enter and offer our humanity.” This image of the closing of these gates is meant to inspire us to commit to repentance, to try to change and do better in the coming year. The gates have now closed. And so we must be resolved to commit to change.

But does the calendar, and most especially this month of Tishrei, even leave us time to do the hard work of repentance?

Perhaps the answer can be found in the somewhat obscure holiday of Hoshanah Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot. The rabbis suggest that these gates of repentance do not actually close on Yom Kippur but instead on this penultimate day of Sukkot. Sukkot becomes not just a celebration of God bringing us out of Egypt, but an extension of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It’s as if the tradition reminds us that God knows the assignment is incomplete. God grants the students an extension. We have some more days to fix things, to start anew.

We are then reminded of an essential truth. The assignment is always incomplete. We always have to fix ourselves. We always have to change. We always have to recommit ourselves to repair.

Despite all the pledge to do better on the days just past, this job is always incomplete. Our commitments to do better are often just as temporary as the sukkah’s flimsy roof that cannot even keep out one drop of rain. Still God is always waiting for us to do better. And God keeps extending the deadline. God keeps hoping we can do better.

The gates of repentance remain forever open.

Such choices are of course not in our hands. And so one major holiday comes in quick succession, one right after another. We barely have enough time to come up for air. We turn from the beating of our chests and recounting of our sins on Yom Kippur to the banging of hammers as we put up our sukkahs and then the hosting of elaborate get-togethers in these temporary booths which signify the Israelites wandering through the desert wilderness. Why do we so quickly move from one major holiday to another? Why is this Hebrew month of Tishrei so demanding?

We only just gathered for the beautiful and concluding Yom Kippur Neilah service. As the gates of repentance are about to close, we prayed, “Open for us the gates of repentance and return, that we may enter and offer our best. Open for us the gates of forgiveness, that we may enter and offer our humanity.” This image of the closing of these gates is meant to inspire us to commit to repentance, to try to change and do better in the coming year. The gates have now closed. And so we must be resolved to commit to change.

But does the calendar, and most especially this month of Tishrei, even leave us time to do the hard work of repentance?

Perhaps the answer can be found in the somewhat obscure holiday of Hoshanah Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot. The rabbis suggest that these gates of repentance do not actually close on Yom Kippur but instead on this penultimate day of Sukkot. Sukkot becomes not just a celebration of God bringing us out of Egypt, but an extension of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It’s as if the tradition reminds us that God knows the assignment is incomplete. God grants the students an extension. We have some more days to fix things, to start anew.

We are then reminded of an essential truth. The assignment is always incomplete. We always have to fix ourselves. We always have to change. We always have to recommit ourselves to repair.

Despite all the pledge to do better on the days just past, this job is always incomplete. Our commitments to do better are often just as temporary as the sukkah’s flimsy roof that cannot even keep out one drop of rain. Still God is always waiting for us to do better. And God keeps extending the deadline. God keeps hoping we can do better.

The gates of repentance remain forever open.

FOMO is a Real Thing

What follows is my Yom Kippur morning sermon.

On this Yom Kippur I wish to speak about the inner life. In particular I want to talk about fear. It is real. It is pervasive. We are frightened by a resurgent antisemitism. And to be sure, I spent plenty of time talking about antisemitism and how we might battle it on Rosh Hashanah. We are afraid of terrorism and wonder where the next attack might be. 9-11’s wounds still run deep. Our children are terrified by climate change and speak about the rising of the oceans as if it’s already happening here on Long Island. Our parents are nervous about the economy and watch the stock indexes as if their very next meal depended on it. We are nervous about our children getting into college or getting into too much trouble when they are away at college or later, traveling by themselves throughout this broken world or then finding a job that they will find fulfilling and meaningful. We read about the latest threats to our health, which medicines might cause cancer and which habits might shorten our years. We are afraid of strangers and time after time, decide we would rather go out with trusted friends rather than going someplace new and meeting new people. Need I go on—again? There is an endless list. Each of us could add plenty of items to the compilation. Each of us carries a host of fears in our hearts. And, I could on this Yom Kippur day explore any one of these challenges, and fears. That is not my intention. Instead I wish instead to speak to how are we going to manage this fear. I wish to continue the discussion we began on Rosh Hashanah evening. Where are we going to place these overwhelming fears? How are we going to move forward without being consumed by them? How can we no longer be ruled by our terrors?

Our tradition offers some guidance. That, as you might expect, would of course by my perspective. It stands to reason that a rabbi would think Judaism has the answers. Let’s first examine these days, called Yamim Noraim, days of awe. But the Hebrew word for awe, yirah is the same as it is for fear. These days could also be translated as days of terror. There are any number of our prayers that invoke fear. “On Rosh Hashanah this is written, on the fast of Yom Kippur this is sealed, how many will pass away from this world, how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die…” Thank God the cantor sings this prayer to an upbeat tune. “B’rosh hashanah yikateivun…” (And thank God the cantor sings it rather than me.) The music is an antidote to the prayer’s literal meaning. Do we even believe such words, “…who by fire and who by water, who by war and who by beast, who by earthquake and who by plague…”? Are they meant to frighten?

According to legend this Unetanah Tokef prayer was authored Rabbi Amnon, an eleventh century Jewish leader living in Mainz, Germany, who was brutally tortured and martyred. Prior to his death, during these very days, he offered these words, “Unenatanah tokef kedushat hayom.” And that, quite frankly, just makes this prayer all the more frightening. “B’rosh hashanah yikateivun…” And that of course brings me to one answer of how we should confront fear. Sing! Sing loudly. Clap your hands and dance. I’m not saying ignore the terrors. But music has a way of healing. It has a way of even banishing fear or at the very least helping us to forget them for a little while.

No rabbi exemplifies this more than the Hasidic giant, Rebbe Nachman of Bratslav. He was the great grandson of the movement’s founder, the Baal Shem Tov. If you have been to Israel, his followers are those hippie like youth who park their colorful van with large speakers on top, and sing and dance wildly on Ben Yehuda’s streets. Their goal is to allow God’s magnificence to overwhelm all other worries. You can’t get too afraid if you are dancing. Yirah, fear, must be understood as awe. They might even argue that fear of God is a good thing, and a good fear. If that terrifying Unetanah Tokef prayer motivates you to do good, to correct your wrongs and do better, then what’s wrong with that kind of fear? It can be motivating. It can even be edifying. But that’s not how I like to do things—not the dancing part—but the fear as a motivation part. Then again if that’s how the right thing gets done the tradition will take it. Personally, I prefer to understand yirah as awe and to try to infuse as much of life with the feeling of “that’s awesome.” Sometimes it does require a good deal of singing and most especially dancing. That’s the medicine. You have to get out there and move.

Among Rabbi Nachman’s most famous sayings is: “Kol ha-olam kulo, gesher tzar maod, v’haikar lo l’fached klal—the whole world is a narrow bridge and the most important thing is not to be afraid.” It seems that Nachman did not just sing and dance. He was not oblivious to fear. The world does not always appear so wonderful. Sometimes it is constraining. At times it is narrowing. Summon the strength and walk forward. Do not be afraid. Easier said than done, Nachman. Sometimes we want to just curl up and not even look at that bridge. Sometimes we just want to turn around and walk in a different direction.

We walk the other way most especially when asked to meet new people. We would rather just hang out with friends. We would rather just go out with people we have known for years. It feels—well, safer. Judaism urges us to love our neighbor. V’ahavta l’reecha kamocha. But how many of us actually even know everyone who lives on our block? What about the people living down the street? How about those who live on the other side of town? How often have we actually struck up a conversation with someone standing in line next to us? Love the neighbor. But they could be different. They could even be dangerous. I get it. The Hebrew word for neighbor has embedded within the word for evil, rah. It’s a fine line. They could be strange. They could have ideas different from our own. And so, we retreat to known acquaintances. We withdraw to like-minded conversations.

Nothing has injured the bonds that can be made between neighbors, between those standing right by our side than that thing we clutch most tightly in our hands as if it is a lifeline. I am talking about the cellphone. We stand in line, with our earbuds in our ears, talking to friends miles away. We text people who may in fact be on the other side of the world but miss out on making a new friend who could be standing by our side. The world, and its myriad of people, and its possibilities for new friends and new discoveries, await us, but we scroll through Instagram photos posted by well tested friends or to make sure we have not missed out on some big event or some gathering. “Really Jenna was invited to that party. How come I wasn’t?” Snap a sad face to some of your friends to make sure they also were left out. It’s crushing. Look up. The sun is still shining. The sky is blue. Put on a song. Start tapping your feet and dance. Talk to the person standing next to you.

There is a fear that is driving all this. And it is called FOMO. Yes, my young students, you thought I was not paying attention. Fear of Missing Out seems to drive much of what we do. And it is real. I am not all suggesting, nor do I believe, that we should get rid of our iPhones. But we have to figure out how to use them and how not to be so dependent on them. They are extraordinary innovations. Who can imagine navigating traffic without Google Maps or doing homework without Google Translate? Who can imagine not being able to text or WhatsApp someone regardless of the time zone they are in? Then again try talking some more to the person who sits by your side, in the same time zone. For all the connectedness the cellphone provides we now recognize it causes a great deal of loneliness. And that is because people need connections in real time. People need words spoken to them and spoken with them. They need to look at each other when they are trying to say something really important, or something really difficult, like “I’m sorry.”

I have a crazy idea, albeit an old fashioned one, but one that I most especially hope my young students heed. As opposed to taking so many selfies of yourself in this place or that, text your friend the following words “I can’t wait to see you and tell you about this beautiful place I am visiting right now or this amazing experience I am having right now.” And then are you ready for this, when you see them, use your words to paint a picture of that place or that experience. Try doing that without scrolling through your photo roll. Because then you can fill in the nuance, the good moments as well as the bad. Have you ever seen my Facebook feed? It’s only pictures of me smiling, as well as of course a lot of blog posts and articles that I find thought provoking. Those pictures are all curated happiness. They’re just snippets of laughter and smiles. That’s not all there is to life. But this is what we do now. We accumulate “smile for the picture” snapshots and then what do we do next. We delete every picture from the photo roll that is not perfectly flattering.

That’s not real life. Reality is when you sit down with a friend and you talk about the good and the bad; it’s when you tell stories; it’s when you hug and when you hold people close. It’s when you open your heart to meeting new people and learning from other people. There have been recent studies that indicate the iPhone suppresses compassion. One study even found that when people are sitting around a table together, but leave their phones on that same table, their empathy and concern for others are diminished. I am just as guilty as the next person. “Why hasn’t Ari texted back? Oh my God. I hope he’s ok.” It’s been…five minutes already. I better check Find my Friends.